For the longest time we’ve had this idea, of turning one of our most-used Swift Collection Types into a simple one-instruction comparison call, down at the assembly level, to check whether an element belongs to or not in a Set-like data structure.

This is the tale of how and why nRF Connect for iOS uses said modified Set-like Collection Type, and the rabbit hole we went down to put that idea to rest.

The Start

As we have mentioned in other texts, nRF Connect for iOS 2.x follows the Unidirectional Data Flow (UDF) paradigm. We do this without the use of Apple’s own tools, such as Combine, because thus far we have chosen to support all iOS devices running on iOS 9 and newer. What it boils down to, is that nRF Connect is built around one or more Single Source(s) of Truth, called Data Store(s), which handle specific parts of app’s logic, away from all of the User Interface complexity. These stores are all Grand Central Dispatch-protected entities, availalbe to our UIViewController(s) and UIView(s) through an AppContext struct.

The Data Store(s) need to be saved to disk at regular intervals, because they contain important information that we don’t want to recreate using default values, such as Advertisers and Settings. And to keep the code as simple and reusable as possible, we elected to use Swift’s Codable protocol for automatic storage in JSON format. Whilst easy and simple to use, this JSON format has its drawbacks; namely, that it can cause the amount of data we have to write to balloon in size pretty quickly.

Rise of the OptionSet

One of the things all of us do in our apps is to check for elements belonging to a Collection, for which the obvious solution would be the use of a Set data structure, which provides us with O(1) constant-time to verify whether an element is present.

The following state, tracking a device's @appearance property, belongs to one of our Data Store(s). We use this, for example, to determine whether a device passes a Filter, such as having DFU capabilities. Hence, why we'd need to store this information in a Set to make this operation fast. This is how a Set<Bluetooth.Appearance> would be saved to disk in JSON form:

appearance: [

thingy, dfu, mcumgr

]

This is acceptable, of course. But we were not satisfied with it. Multiple structures in nRF Connect used a similar data representation based on enum values, and it felt like a small-enough problem to tweak and play with that no matter how much we screwed up, we could find our way out of it. Which, we agree, is the very definition of fixing something that isn’t broken. Furthermore, no matter what we choose to do to optimise this use case, the inherit verboseness of the JSON format would render all of our efforts irrelevant. After all, what difference does it make to save a few characters in one section, when in another, the Codable protocol will we auto-generate 5 times the number of boilerplate text?

If you think about it in this way, the path we’re embarking on does not make any sense. But, programming is also an art form. And in our opinion, as a programmer we should also attempt to have a bit of fun and learn new things along the way. So we started looking for ways to do better. One way we could reduce the number of characters required to represent a Set of elements, was to make their RawRepresentable type an Int. This would yield the following kind of change:

appearance: [

1, 3, 4

]

Not bad. However, we decided to go one-step further (the theme of this blog post), and inspired by NSHipster’s OptionSet data structure, we went ahead and defined an OptionSet as a struct containing a Set of elements conforming to the new Option protocol.

protocol Option: RawRepresentable, Hashable, CaseIterable {}

struct OptionSet<T: Option>: Hashable, Codable, ExpressibleByArrayLiteral {

private var set: Set<T>

}

In both Swift’s definition of an OptionSet and NSHipster’s, an OptionSet is defined as a collection of values that we choose to represent via a bit extension of its @rawValue property. So if the thingy enum case’s @rawValue is ‘1’, in the OptionSet it’d be represented as 2 << 1, meaning ‘2’. Applying NSHipster’s OptionSet without any more changes, would lead to the following result after being serialized as JSON:

appearance: [

2, 8, 16

]

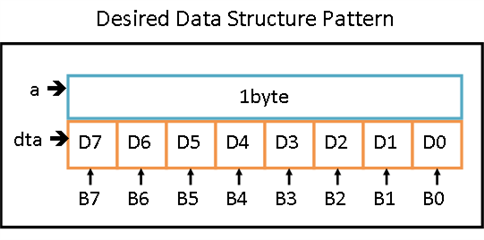

Baring some extra computation, this is exactly the same result as Swift’s Set. But we can do better. Inspired by how a Status register works in a CPU, we can use a bit to represent whether an element is present or not in the Set. And because we are representing each possible element’s @rawValue as a power of two value, no two elements will overlap, because each one is represented as a bit being set in an integer value, like a CPU’s Status register, where each bit designates a certain condition, with ‘0’ meaning the absence of such condition, and ‘1’ its presence.

Source: Curly Brace Coder

This means it should be possible to reduce the appearance field in JSON like this:

appearance: 26 // 2^1 (1 << 1) + 2^3 (1 << 3) + 2^4 (1 << 4)

This is how:

extension Set where Element: Option {

var rawValue: Int {

var rawValue = 0

for (index, element) in Element.allCases.enumerated() {

if self.contains(element) {

rawValue |= (1 << index)

}

}

return rawValue

}

}

That is, we’re taking the @rawValue of each Option and adding it to form the @rawValue we encode as JSON. With this extension, and a little bit of Codable Protocol trickery involving a custom init() to reverse this effect, we can get an OptionSet to encode and decode itself from a rawValue in this manner.

There are caveats, of course – we need to guarantee Unsigned Integer (UInt) RawRepresentable values, or else this bit-logic does not make a lot of sense. And also, we must take care that in each OptionSet, its Generic Type has as many possible values as bits on every CPU register (CPU word size) or less. Otherwise, we’d be stepping into the world of double-word operations, which are more expensive.

Note: If you need a quick refresher on how a CPU works, this video might be useful.

If this works, what else is there to do, then?

For the longest time, we were happy with this arrangement. The code worked, and it was solid to a fault. The use of OptionSet was extended across previous features when we first implemented it, then onto new features. Bugs and crashes were found, but none ever caused, or even remotely related, to our custom OptionSet implementation.

However, we still had this dangling idea on our minds. “If our OptionSet was so efficient, why did we have to rely on a Set for its implementation?”

Think about it. If we are mimicking’s the CPU’s behavior, why do we need a higher-level abstraction type, such as a Set, to check whether an element is present or not? We can just do it the same way the CPU checks its own Status register: using an Unsigned Integer, we can represent each value being a part of the Set by its corresponding bit being set to ‘1’. We already have the code to represent an element as a bit, and it works. And to check whether an element is present, all we have to do is perform a bitwise AND operation to check whether its corresponding bit is enabled. Excusing the overhead introduced by a higher-level programming language like Swift instead of C/C++, the comparison check itself should be reduced to a single instruction - no overhead !

In other words, we’d go from this:

func contains(_ member: T) -> Bool {

return set.contains(member)

}

To this:

typealias RegisterValue = UInt

extension Option where RawValue == RegisterValue {

var bitwiseValue: RegisterValue { 1 << rawValue }

}

struct BitField<T: Option>: Hashable, Codable, ExpressibleByArrayLiteral where T.RawValue == RegisterValue {

private var bitField: RegisterValue

…

func contains(_ member: T) -> Bool {

return bitField & member.bitwiseValue == member.bitwiseValue

}

…

}

As for item insertion and removal, we just need to add and substract the power-of-two value of the element’s @bitwiseValue, which is the same as turning on and off that bit. Like so:

mutating func insert(_ newMember: T) {

precondition(newMember.rawValue < RegisterValue.bitWidth)

guard !contains(newMember) else { return }

bitField += newMember.bitwiseValue

}

mutating func remove(_ member: T) {

precondition(member.rawValue < RegisterValue.bitWidth)

guard contains(member) else { return }

bitField-= member.bitwiseValue

}

Wait a minute! That’s not a lot of fun now, is it? If we need to turn on and off a single bit, why don’t we just use the XOR operation instead?

mutating func insert(_ newMember: T) {

guard !contains(newMember) else { return }

flip(newMember)

}

mutating func remove(_ member: T) {

guard contains(member) else { return }

flip(member)

}

mutating func flip(_ member: T) {

precondition(member.rawValue < RegisterValue.bitWidth)

bitField = bitField ^ member.bitwiseValue

}

And with these ingredients put together, we are free to kill the Set used as the internal data structure, and just use a CPU word - a UInt which we aliased as RegisterValue - as storage. This use of an Integer of CPU Register/Word size (64 bits in a 64-bit machine architecture), to represent types of known bit-width, all fitting within the CPU’s Word size, is known as a BitField.

In theory, this change should give us multiple advantages. For one, the code should be faster, because Set is designed to work with any Generic type conforming to the Hashable protocol. Since we only need bit-wise comparisons, we are getting rid of a lot of extra code and API we don’t use from the Swift Standard Library Set. Also, it’s possible LLVM could reduce the in-memory size of our entire BitField to a single CPU register word size: 64 bits in the case of modern Macs and iPhones/iPads (ARM included). We don’t know how much added complexity the Swift Standard Library’s Set means in terms of memory use.

We are not going to lie, though: completing this transition was not that easy. Not because of the logic pertaining checking for insertion, removal and existence of an element, but because we’d used our internal Set to make OptionSet conform to the Collection protocol. When it was time to adapting BitField for Collection conformance, it did not work. Most of it was because we did not understand the API regarding Collection indices, so we had to learn, and a change tactics towards copy/pasting some blind code from StackOverflow (kidding). And as usual, headbutting ourselves against when and how the endIndex should return for the Sequence/Collection protocol to understand when a BitField was over, or when it was empty, took an hour of slamming our expensive gaming keyboard on our table, plus 15 seconds of mental brilliance in which we not only solved the entire issue, but also deleted a lot of unnecessary code.

And You Did All of This For...?

Wait. Just wait until you see this. With our new BitField structure working, with its Unit Tests verifying it, plus all of nRF Connect's massive suite of Integration Tests confirming most of the app’s features worked as expected, we cracked our nuckles and typed in the following in LLDB:

print(MemoryLayout<BitField<Bluetooth.Appearance>>.size) // 8 bytes (64 bits) print(MemoryLayout<BitField<Bluetooth.Appearance>>.stride) // 8 bytes (64 bits) print(MemoryLayout<BitField<Bluetooth.Appearance>>.alignment) // 8 bytes (64 bits)

Aha! Success! Now, let's rollback to a previous commit, so we can compare this to the old and busted OptionSet:

print(MemoryLayout<OptionSet<Bluetooth.Appearance>>.size) // 8 bytes (64 bits) print(MemoryLayout<OptionSet<Bluetooth.Appearance>>.stride) // 8 bytes (64 bits) print(MemoryLayout<OptionSet<Bluetooth.Appearance>>.alignment) // 8 bytes (64 bits)

Uhhhh. That’s not what we were expecting.

But all of this is true. We reached the purported end of the rabbit hole, only to discover our new implementation of OptionSet as a BitField is as efficient memory-wise as the Swift Standard Library tools. When Apple engineers insist on Swift being optimised for our perusal, and that we shouldn’t be worrying about unnecessary tricks, they’re not lying. They mean it.

Saving Grace

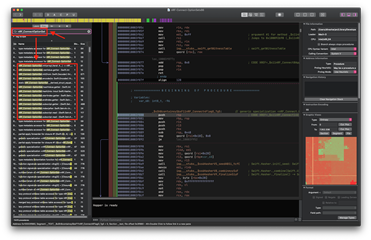

There was one more thing we were curious about regarding the BitField, and that is, how is our BitField translated into assembly code by the compiler? Does it really turn into a single bit-comparison instruction, like we pictured it to be? Or were we also wrong about that?

To verify, we opted for the easiest and simplest path we could think of. iOS apps are not only encripted when compiled and packaged for release on the AppStore, they also have their symbols stripped or mangled, making them harder to reverse-engineer and inspect with tools such as IDA Pro. So we took a different route - we know Apple is transitioning to ARM, but we’re more comfortable with x86-64 assembly, so using this little checkbox that automagically transforms an iOS App into a Mac App, we produced a Mac Release build of nRF Connect, and inspected the code executed for BitField’s contains() function using Hopper:

00000001001ad9f0 push rbp ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV13bitFieldMembers33_7ECDA5C4BCAAD9C5789D6122AEC1A18ALLSayxGyFSbxXEfU_TA+17

00000001001ad9f1 mov rbp, rsp

00000001001ad9f4 push r15

00000001001ad9f6 push r14

00000001001ad9f8 push r13

00000001001ad9fa push r12

00000001001ad9fc push rbx

00000001001ad9fd push rax

00000001001ad9fe mov r15, rdx

00000001001ada01 mov r14, rsi

00000001001ada04 mov r13, rdi

00000001001ada07 mov r12, qword [rcx+0x18]

00000001001ada0b lea rax, qword [rbp+var_30]

00000001001ada0f mov rdi, rdx

00000001001ada12 mov rsi, r12

00000001001ada15 call imp___stubs__$sSY8rawValue03RawB0QzvgTj ; dispatch thunk of Swift.RawRepresentable.rawValue.getter : A.RawValue

00000001001ada1a mov rcx, qword [rbp+var_30]

00000001001ada1e xor eax, eax

00000001001ada20 xor edx, edx

00000001001ada22 cmp rcx, 0x40

00000001001ada26 setg al

00000001001ada29 seta dl

00000001001ada2c test rcx, rcx

00000001001ada2f cmovs eax, edx

00000001001ada32 test al, al

00000001001ada34 je loc_1001ada3a

loc_1001ada36:

00000001001ada36 xor ebx, ebx ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+83

00000001001ada38 jmp loc_1001ada4d

loc_1001ada3a:

00000001001ada3a test rcx, rcx ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+68

00000001001ada3d js loc_1001adaa7

00000001001ada3f cmp rcx, 0x40

00000001001ada43 jge loc_1001ada36

00000001001ada45 mov ebx, 0x1

00000001001ada4a shl rbx, cl

loc_1001ada4d:

00000001001ada4d lea rax, qword [rbp+var_30] ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+72

00000001001ada51 mov rdi, r15

00000001001ada54 mov rsi, r12

00000001001ada57 call imp___stubs__$sSY8rawValue03RawB0QzvgTj ; dispatch thunk of Swift.RawRepresentable.rawValue.getter : A.RawValue

00000001001ada5c mov rcx, qword [rbp+var_30]

00000001001ada60 xor eax, eax

00000001001ada62 xor edx, edx

00000001001ada64 cmp rcx, 0x40

00000001001ada68 setg al

00000001001ada6b seta dl

00000001001ada6e test rcx, rcx

00000001001ada71 cmovs eax, edx

00000001001ada74 test al, al

00000001001ada76 je loc_1001ada7c

loc_1001ada78:

00000001001ada78 xor eax, eax ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+149

00000001001ada7a jmp loc_1001ada8f

loc_1001ada7c:

00000001001ada7c test rcx, rcx ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+134

00000001001ada7f js loc_1001adaa9

00000001001ada81 cmp rcx, 0x40

00000001001ada85 jge loc_1001ada78

00000001001ada87 mov eax, 0x1

00000001001ada8c shl rax, cl

loc_1001ada8f:

00000001001ada8f and rbx, r14 ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+138

00000001001ada92 cmp rbx, rax

00000001001ada95 sete al

00000001001ada98 add rsp, 0x8

00000001001ada9c pop rbx

00000001001ada9d pop r12

00000001001ada9f pop r13

00000001001adaa1 pop r14

00000001001adaa3 pop r15

00000001001adaa5 pop rbp

00000001001adaa6 ret

; endp

loc_1001adaa7:

00000001001adaa7 ud2 ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+77

; endp

loc_1001adaa9:

00000001001adaa9 ud2 ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+143

; endp

00000001001adaab align 16

This is a lot to take in. But we can focus only in what we’re interested in. The first batch of push instructions load the registers with the necessary parameters, so we can skip those. Then, as seen by the comment given to us by Hopper, we can read it’s a call to get the rawValue of the Option Generic, which is the ‘bit’ in the register we need to check against. Following that, there’s the code calculating the @bitwiseValue representative of that Option that we want to AND against, and then, there’s the magic we were waiting to see:

00000001001ada8f and rbx, r14 ; CODE XREF=_$s11nRF_Connect6BitFieldV8containsySbxF+138 00000001001ada92 cmp rbx, rax 00000001001ada95 sete al

This section is pretty much a mirror image of our code:

func contains(_ member: T) -> Bool {

return bitField & member.bitwiseValue == member.bitwiseValue

}

We perform a bitwise-AND, and then compare it. The RBX register contains the BitField’s value, whilst r14 is a parameter pushed onto the stack, so this is the member’s @bitwiseValue already calculated in the register (1 << rawValue), which is AND’ed, and its result stored back into RBX. RAX is also a parameter pushed onto the stack at the start of the call, and judging by the code, we can presume it contains the same value r14 contained, meaning member.bitwiseValue, which is 1 << rawValue’s result. The results of the AND (RBX) are compared (substracted) from RAX (member.bitwiseValue) via the CMP instruction, and if they are equal, the Flags register inside the CPU must get its ZERO bit set to ‘1’ if said element is contained in the bitField, or zero otherwise. A quick StackOverflow search reveals the SETE instruction writes the value of the ZERO flag to the given register, meaning we’re writing into AL the result of the call to the contains() function.

TL;DR: Yes. Our theory regarding LLVM translating our code in assembly down to an AND instruction is true. We haven’t checked if the same thing applies to our XOR operation for insertion and deletion, but it’s safe to presume that’d be the case. Now however, is time to check how the previous iteration of BitField, when it was called OptionSet and relied on an internal Swift Standard Library Set, implements the same functionality:

The first problem we encounter is that … we cannot find the contains() procedure inside the OptionSet. It’s not there. When we looked for its implementation in BitField, we noticed the assembly procedures were defined in the same order as in the source file, so we know where to look. So where is the code? It must exist somwhere. And it does. What we think the Swift compiler is doing is folding the OptionSet into internal the Set itself when compiled, which can explain how the OptionSet struct doesn’t seemingly add any extra baggage in its in-memory representation due to its hidden internal data structure.

So what we can do, instead, is check for the Swift.Set’s contains() procedure, which surely, is the call executed. Searching for a Swift.Set.contains() procedure in Hopper, reveals multiple implementations, or specializations in Swift parlance, of the contains() procedure for each possible Generic Type it's used with, so we’re on the right track. If we check the code of a generic that we use with the OptionSet, like Bluetooth.Appearance whose possible enum values we’ve used as an example throughout the text, we should be looking at the code we want:

int _$sSh8containsySbxF11nRF_Connect9BluetoothO10AppearanceO_Tg5(int arg0, int arg1, int arg2, int arg3) {

rsi = arg1;

rdi = arg0;

COND = *(rsi + 0x10) == 0x0;

if (COND) goto loc_100157732;

loc_100157678:

rbx = rsi;

r14 = rdi;

Swift.Hasher.init(*(rsi + 0x28));

Swift.Hasher._combine(r14 & 0xff);

rax = Swift.Hasher._finalize();

rdx = !(0xffffffffffffffff << *(int8_t *)(rbx + 0x20));

rax = rax & rdx;

if (COND) goto loc_100157732;

loc_1001576c1:

rsi = *(rbx + 0x30);

COND = *(int8_t *)(rsi + rax) == r14;

if (COND) goto loc_100157736;

loc_1001576cb:

rax = rax + 0x1 & rdx;

if (COND) goto loc_100157732;

loc_1001576e3:

COND = *(int8_t *)(rsi + rax) == r14;

if (COND) goto loc_100157736;

loc_1001576e9:

rax = rax + 0x1 & rdx;

if (COND) goto loc_100157732;

loc_100157710:

COND = *(int8_t *)(rsi + rax) == r14;

if (COND) goto loc_100157736;

loc_100157716:

rax = rax + 0x1 & rdx;

if (COND) goto loc_100157710;

loc_100157730:

rcx = 0x0;

goto loc_100157738;

loc_100157738:

rax = rcx;

return rax;

loc_100157736:

rcx = 0x1;

goto loc_100157738;

loc_100157732:

rcx = 0x0;

goto loc_100157738;

}

Now, this is not the assembly code of the contains() function. We’ve gone a different route here, because the assembly code for this function is nearly twice the length as our BitField's. Instead, we're looking at the pseudocode interpretation of this procedure, which is a handy feature of Hopper. Here we can summarise the code as being split into two parts: at the start, we get the parameters, same as our BitField assembly, and then, Set’s contains() calculates the hash value of the value we want to check against. What follows is a series of if-statements and conditions, wherein loc_100157738 represents the code segment to call once the final result is known in the RCX register. Before returning from the procedure, the RCX value is copied (MOVed) into RAX, and then we exit.

TL;DR: yes. It looks like our BitField is shorter, and simpler (less branches & less instructions) when compiled down to assembly. At least in the x86-64 variant as built by Xcode 11.6 under macOS 10.15.

But, is implementing a BitField worth it?

We cannot answer that. This is an area of knowledge you might not want to pursue as a Swift developer, which is fine. We on the other hand, like to be more conscious about the hardware we’re running on, for no other reason that modern processors and compilers won’t make our code run faster if the way we’ve written our software doesn’t match their expectations. But again, this is a choice not all teams can afford to make.

Conclusions

Learning is always fun. And also, next time you open nRF Connect for iOS, and notice that the version number is 2.3.2 or newer, know that yes, besides all the changes listed in the ‘What’s New’ page, your Apple processor is executing a few instructions less, thanks to our BitField implementation.

Top Comments